June 12, 2019

Using Social Media News Posts in Jury Selection (and More)

It is becoming fairly commonplace for trial consultants, attorneys, and other entities to search for potential jurors’ social media presence. However, limiting internet investigations of potential jurors to traditional “Google searches,” Westlaw or similar databases, and searches of social media platforms such as Facebook, LinkedIn, and Twitter, among others, misses an underutilized, but important resource—news media postings on social media. Whether your case is criminal or civil, monitoring and storing relevant posts in their entirety is a must. This applies to both highly publicized and the not-so-highly publicized case. (Those in the latter category—hang tough. We will get there.)

Some Basics About News Media Posting on Social Media

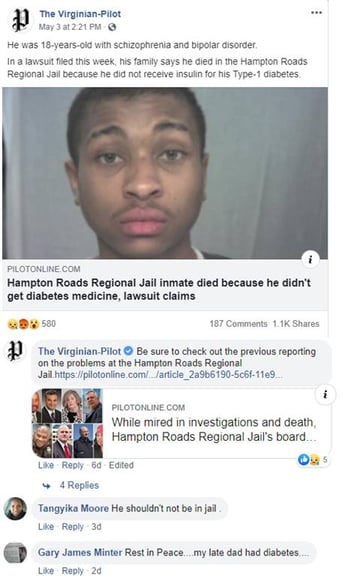

We will consider primarily news media Facebook posts as they tend to be more informative and the usernames are more easily matched to potential jurors. However, some limited information can be derived from tweets (e.g., opinions/comments), if the potential juror’s twitter username is known. When a news source posts to its Facebook page, there are several types of information potentially available. First, there are the “reactions” to the post itself (Facebook currently offers five “reactions,” i.e., like, love, wow, angry, sad, and haha/laughing). Second, there are “shares” of the post to other Facebook users with those users having the opportunity to comment/reply and register a reaction. Third, there are the comments and replies to comments associated with the post. Finally, readers can register their reactions to both the comments and replies. Consider the following example involving a recent post on The Virginian-Pilot Facebook page regarding the filing of a lawsuit over the death of an inmate.

"Deconstructing” a Media Post

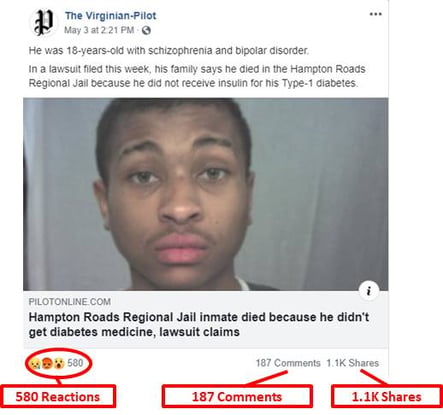

To understand the scope of information available, let’s deconstruct the above post to see what information is available. As shown below, there is the “top line” information about the post. This information shows that (a) 580 individuals have registered their reactions to the post; (b) 187 comments/replies were posted; and (c) the post was shared approximately 1,100 times.

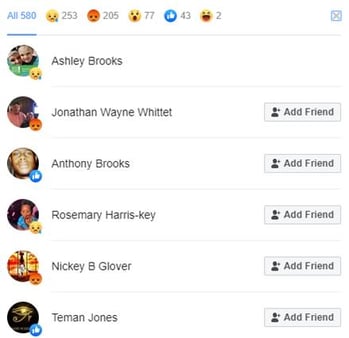

The next phase of the deconstruction process concerns the “reactions” to the general post. Facebook allows us to see the type of reactions to the general post and who posted the reaction (depending on the user’s privacy settings), which in this case shows us that there are 253 sads, 205 angrys, 77 wows, 43 likes, and 2 hahas.

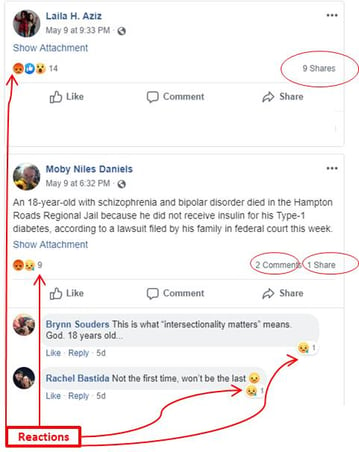

Continuing the deconstruction process reveals that there were approximately 1,100 shares. An example of these shares below shows that not only are the shares displayed (subject to privacy settings), but also comments, replies, reactions, and additional sharing of the post are possible.

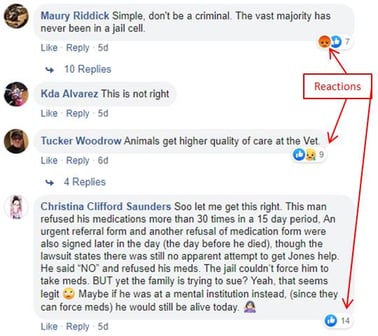

The final step in the deconstruction process concerns the comments and replies to the post. There were 187 comments (actually comments and replies). A vast majority of these comments and replies were supportive of the plaintiff (holding the jail responsible for the outcome), with a minority of individuals responding in a pro-defense manner (e.g., “Simple. Don’t be a criminal” and “. . . The jail couldn’t force him to take meds. BUT yet the family is trying to sue? Yeah, that seems legit. ” The not fully expanded comments section below illustrates these points.

Whew . . . Okay, Now, What Do You Do with This?!

The information gathered from news media posts on social media can address two major questions: (a) How does the community feel about the case? and (b) Have any potential jurors interacted with posts relevant to the case? The former question focuses on trial preparation, and the latter question focuses on jury selection.

Trial preparation. Knowing how the community reacts to the case can help in several ways, provided certain basics are understood. These basics recognize the limitations of viewing data from self-selected samples (i.e., individuals choosing to visit a Facebook page and respond versus seeking reactions from a random sample of community residents). First, is the media source a neutral source of information (e.g., general major news media sources) or does the media source exhibit leanings toward a certain political or social viewpoint (e.g., FOX News, Breitbart News, MSNBC, or HuffPost)? Second, and related to the first question, does the news media source serve the general population or a self-selected subpopulation that must be taken into account when considering this information (e.g., the source of the comments, replies, and reactions)? These two questions determine the generalizability of the findings from such research.

Taking into account the sampling issues, the information obtained can be helpful in trial preparation in several ways. First, based on the overall distribution of positive and negative comments, replies, and reactions, a picture develops as to how the community (if only the news media source’s community) views the case. Second, based on the content of the comments and replies certain themes may be supported or significant questions may have been raised that can be addressed in discovery and/or trial. Third, the comments and replies can serve as the basis for important voir dire questions, e.g., “How many of you feel that an inmate or his family should not be allowed to sue the jail when the inmate refuses medications which leads to significant health problems or death?” Finally, in some cases it is possible to examine the Facebook pages of those who provide comments, replies, and reactions and discover commonalities (e.g., common likes, interests, and activities) among jurors who favor one party or another. These commonalities can be used when researching potential jurors’ Facebook pages to help evaluate the favorability of potential jurors.

Jury selection. Of great concern in jury selection is whether potential jurors have been exposed to publicity related to the case and, as a result, have formed opinions concerning the case or its parties. Posts by news media on their social media pages need to be checked to see (subject to privacy settings) if potential jurors have interacted with case-relevant posts (e.g., made comments or replies, or shared posts, or registered reactions to the posts, or their associated comments and replies). Both our own research and news reports have revealed potential jurors interacting with case-relevant internet websites/social media pages. For example, in a 2018 murder trial in Georgia, a trial juror was found after trial to have made comments six to seven months ahead of trial concerning the criminal defendant (e.g., “. . . So hell yeah, she’s GUILTY. It doesn’t take a genius to see this!!!”). (A mistrial was declared because the jury was unable to reach a verdict. The defendant was subsequently convicted at retrial. However, the defendant has sued the juror for defamation in connection with the above-referenced post.)

The above example illustrates the need to cross-check potential jurors’ Facebook usernames with media posts. However, as with life, it is never that simple. Current Facebook tools do not allow for the searching of media posts using the jurors’ usernames. While you may “see” the username associated with the comment or reply, it is not subject to a successful search; only the text of the comment or reply is searchable. Also, the reactions to the general post and reactions to comments and replies are not searchable as they appear in the Facebook post.

A remedy. Fortunately, there is a strategy to overcome these limitations in searching on news media social media pages. However, it often requires considerable efforts being made in advance of trial, particularly when there are numerous news posts and/or substantial activity involved with relevant posts. All relevant posts must be deconstructed (or expanded) and placed in a searchable database. All of the elements discussed above in the deconstructing posts section must be copied and stored in searchable databases. (As our clients know, this is no small task in cases involving posts containing hundreds and even thousands of reactions, comments, replies, and/or shares.) In this manner, juror usernames can be quickly searched in these databases and “hits” can be recorded for use in voir dire and jury selection.

So, I Can Wait Until Trial To Do This, Right?

No. It is tempting to wait until just before trial to see if there really is a need to do this research. Unfortunately, the internet waits for no one. News social media pages are constantly being updated with new posts. Sometime between a couple of weeks and a couple of months, the number of older posts on the timeline is reduced, leaving “highlights” or selective posts, so that earlier posts may or may not appear when scrolling down the timeline to find relevant posts. The good news: you can use the news media page’s search bar to find posts that are cataloged and still available (posts dating back numerous years simply may not be recoverable). The bad news: if your search terms do not include the exact or, in some cases, similar terms found in the post’s title or short text of the post, relevant posts may remain hidden. Given that media coverage of the critical event(s) and subsequent developments in the case usually occur months or even years before trial, constructing a database containing relevant posts should begin soon after the initial event (e.g., media coverage of the crime, accident, or filing of the lawsuit). Ideally, such “scrapping” should be done after a short period of time has elapsed (e.g., 14 days) to enable inclusion of all contact (e.g., reactions, comments, replies, and shares) with the post. For example, a recent post concerning a controversial lawsuit saw reactions and comments rise from 340 reactions and 128 comments within 12 hours to reach and stabilize at 15K reactions and 1.9K comments after eight days.

Wait . . . What About Not-So-Publicized Cases?

As I mentioned in the beginning, the approach described also applies to those cases not receiving considerable media attention. Just because a particular case (e.g., excessive force, medical negligence, murder, or political corruption) may not receive media attention does not mean there is nothing to be gained in utilizing the above approach. Searching news media social media posts using terms relevant to your case (or similar cases that have received publicity) can yield valuable information. Individuals (and potential jurors) commenting on other excessive force cases (e.g., pro- or anti-law enforcement or victims of police violence) or comments about other lawsuits (e.g., greedy plaintiff lawyers or plaintiffs) or comments about the opioid lawsuits (e.g., Big Pharma is at fault or it is the fault of those who chose to abuse opioids), or comments about criminal cases (e.g., the defendant should be given the death penalty) can indicate relative desirable and undesirable opinions that could apply to the instant case.

Final Notes

There is an additional value to researching the social media posts of news media. As I have discussed in previous posts, jurors are not always candid and forthcoming in their answers to voir dire questioning. In particular, jurors may not report having formed or having expressed an opinion concerning the case. The Georgia murder case discussed above is likely a case in point, provided appropriate questions were asked on voir dire. Possession of evidence that contradicts jurors’ assertions of lack of familiarity with the case or lack of opinion formation would be vital in identifying (within privacy setting limitations) any potential jurors who have interacted with the news posts. In addition, it is possible that even if potential jurors downplay any opinions formed, their failure to respond affirmatively when asked about their contact with any news posts, and their interactions with the post (e.g., registering reactions or leaving comments or replies) could serve as the basis for their removal for cause (or peremptorily) because of their failure to answer honestly to a material question on voir dire.

Since judges will be deciding on relevant jury selection issues posed by social media contact and activity, it is necessary in many cases to educate these judges as to the issues involving social media. Many, if not most, judges are not familiar with social media or, if they are, it is on a very basic level. Making judges aware of social media issues in advance of jury selection could go a long way to sensitizing them to relevant concerns. Waiting until something happens during jury selection may leave the judge in a position of making a ruling without fully appreciating social media information.

Finally, with 69% of U.S. adults using Facebook (and 74% of those using it daily) and social media expansion as a source for news (it now surpasses print newspapers), greater attention will need to be paid to these platforms as it pertains to litigation preparation and jury selection.

Mastering Group Voir Dire Tip Series:

Check out our Mastering Group Voir Dire Tip Series in this blog and learn approaches and techniques that will help you be more effective in your next jury selection. Also, for short videos concerning these tips, see an introductory two-minute video, Tip 1, Tip 2, Tip 3, Tip 4, Tip 5, Tip 6, Tip 7, Tip 8, Tip 9, and Tip 10.

For more information on voir dire and jury selection, see Mastering Voir Dire and Jury Selection: Gain an Edge in Questioning and Selecting Your Jury, Fourth Edition (2018). Also, check out my companion book on supplemental juror questionnaires, Mastering Voir Dire and Jury Selection: Supplemental Juror Questionnaires (2018).

Available podcasts:

On January 25, 2019, Dr. Frederick presented a CLE program entitled, “Mastering Voir Dire and Jury Selection” at the ABA Midyear Meeting at Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas. Legal Talk Network conducted a short, 10-minute interview in conjunction with this program. You can listen to this podcast at: https://legaltalknetwork.com/podcasts/special-reports/2019/01/aba-midyear-meeting-2019-mastering-voir-dire-and-jury-selection/.

Dr. Frederick presented a 60-minute program based on his book Mastering Voir Dire and Jury Selection: Gain an Edge in Questioning and Selecting Your Jury for the ABA Solo Small Firm and General Practice Division’s November 21, 2018 session of Hot Off the Press telephone conference/podcast. Check it out at the Hot Off the Press podcast library at: https://www.americanbar.org/groups/gpsolo/podcasts/2018-podcast-library/